Final Writeup

Lambda++ is a C++ parallel programming library designed to run across a cluster that achieves near-optimal speedups while enabling programmers to write concise, functional code. We achieve these speedups using a variety of techniques, including static cluster profiling, work balancing, and multi-level parallelism within the cluster.

Abstraction

Lambda++ presents two abstractions. The Cluster abstraction is used to initialize and tear down a cluster.

The core of the library, the Sequence abstraction, is basically an ordered

list of elements that supports operations like map, reduce, and scan. All of

these operations take in arbitrary functions (thanks to C++11’s new syntax for

lambda functions) and work with arbitrary types (due to C++’s template system).

More precisely, the Sequence abstraction is inspired by 15-210’s SEQUENCE

signature for SML. The Sequence class declares a number of higher order

functions which allow users of the library to express their algorithms in a way

that is both expressive for the algorithm designer as well as easily

parallelizable by the library authors. For the purposes of our analyses, we

implemented a subset of the SEQUENCE functions, including

mapreducescantabulate, implemented as a C++ constructor

as well as 3 additional functions not in the 15-210 SEQUENCE signature:

transform, an in-placemapgetandset, which load and modify (respectively) the value at an index

Operations like map, tabulate, and transform are completely data parallel.

However since they take in arbitrary functions, it’s possible for the workers to

diverge in the amount of work done per input, so we put in extra effort to

balance the load across workers to equalize these divergences. We took a similar

approach with reduce and scan, though these functions have a larger

proportion of serial work load (i.e., they have logarithmic span).

Example Code

Our library makes it easy to write parallel programs. Here’s an example:

/*

* Test if a sequence of 1's or -1's is "matched", treating

* 1's as open parens and -1's as close parens.

* (String parsing omitted)

*/

bool paren_match(Sequence<int> &seq) {

// C++11 lambda functions

auto plus = [](int a, int b) {

return a + b;

};

auto min = [](int a, int b) {

return a < b ? a : b;

};

// Compute a prefix sum

seq.scan(plus, 0);

int int_max = std::numeric_limits<int>::max();

// A well matched sequence has a net sum of 0 and

// never drops under zero

return seq.get(seq.length() - 1) == 0 &&

seq.reduce(min, int_max) >= 0;

}

To launch the above program:

#include "uber_sequence.h"

#include "cluster.h"

int main (int argc, char *argv) {

// Start the Cluster

Cluster::init(&argc, &argv);

// Make Parentheses sequence ()()()()()()...

auto generator = [](int i) { return i % 2 == 0 ? 1 : -1; }

int n = 200000000;

UberSequence<int> seq = UberSequence<int>(generator, n);

// Run paren match code, assert the sequence is well matched

assert(paren_match(seq));

// Destroy the Cluster

Cluster::close();

return 0;

}

Here’s a more complicated function that solves a classic dynamic programming problem: the knapsack problem. Suppose you have N items, each with a weight and a value. You have a knapsack that can hold up to weight W. Find the maximum value you can carry.

int knapsack (UberSequence< pair<int, int> > *items, int weight) {

// Return the max of 2 integers

auto intMax = [](int x, int y) { return max(x, y); };

// money[i] stores the optimal value you can carry

// if you have a knapsack that holds up to weight i

int money[weight+1];

// If you can't hold any weight, you get 0 value

money[0] = 0;

// Classic DP solution that uses solutions to previous sub-problems

for (int i = 1; i <= weight; i++) {

money[i] = 0;

// For an item K, find the best value we can get if we use item

// K in a knapsack of weight i

std::function<int(pair<int, int>)> bestUsing = [&](pair<int, int> item) {

if (i - item.first < 0) return 0; // Out of bounds

return money[i - item.first] + item.second; // Use solution to sub-problem

};

Sequence<int> *bests = items->map(bestUsing);

// Get the best item to take in the knapsack of weight i

money[i] = bests->reduce(intMax, 0);

// Free the sequence we created

delete bests;

}

return money[weight];

}

The knapsack problem is relevant to many real world applications including optimization problems of finding the least wasteful way to cut materials.

Implementation

Arbitrary Lambda Functions

All code outside of calls to the Sequence library is executed identically by every node in the MPI cluster. This allows the Sequence library to operate on generic functions (even those that require “variable captures”), since every node has access to the same data. When a Sequence library method is called, the nodes operate on different parts of the sequence, and so the execution paths (of nodes) diverge. At the end of the Sequence library call, we ensure that all data outside of calls to the Sequence library is the same across nodes. The nodes resume executing code outside of the Sequence library identically (the execution paths converge).

A huge advantage is that the above ‘symmetric’ architecture allows for arbitrary lambda functions. Most other architectures require communicating lambda functions across nodes. Since C++ is a compiled language, it’s almost impossible to send arbitrary lambda functions from one node to another. One possible ‘hack’ is to bitwise copy the lambda function, but the resulting code would not be portable (since the way the lambda function is stored is implementation defined).

Disadvantages: Since code outside of the Sequence library is duplicated, the setup could be energy inefficient. However, this issue can be resolved if the user uses our abstractions only in the parts of the workload he wishes to parallelize. Another issue is that code outside of the Sequence library must be deterministic (e.g. the user can’t get the system time, or call random number generators). This can be solved by providing the user with libraries for such use cases. A bigger issue is that we were not able to implement Sequences of sequences using this architecture, and we are not completely sure if it is feasible. This is left as future work. We think most workloads can survive without having to create multi-level sequences.

Work Balancing

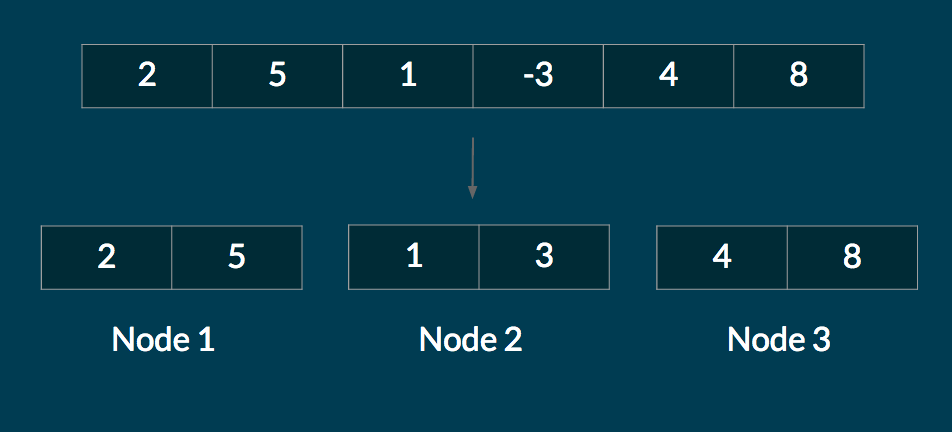

The naive way to distribute the sequence across the cluster is to partition the data evenly, as shown below.

However, in many workloads, certain parts of the sequence require a lot more compute than other parts of the sequence. For example, if mapping a function on the above sequence required a lot more compute time on the last 2 elements, Nodes 1 and 2 would finish their computations long before Node 3. In effect, Node 3 would be a bottleneck.

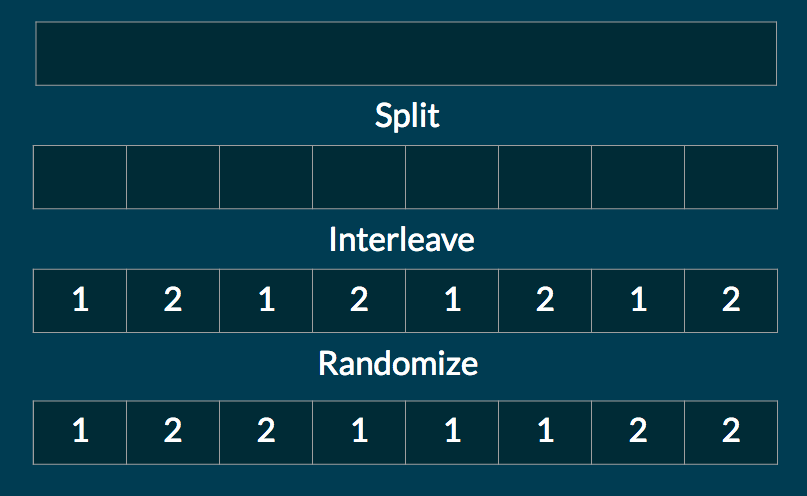

Our work distribution avoids this problem. First, we partition the sequence into many more chunks than there are nodes (in current implementation, roughly 5 times as many). Each node gets an equal number of these small chunks. However, the allocation of chunks to nodes is random.

If the number of nodes is large, this scheme balances load well for most real life workloads. There are cases where our work allocation method will not perform optimally, for example if a single chunk in a sequence requires much more compute than the rest of the sequence. In these cases, a work stealing or dynamic chunking approach might be better. But for most real life workloads, we think our method achieves effective load balancing without incurring the large overhead of dynamic schemes.

Cluster Profiling

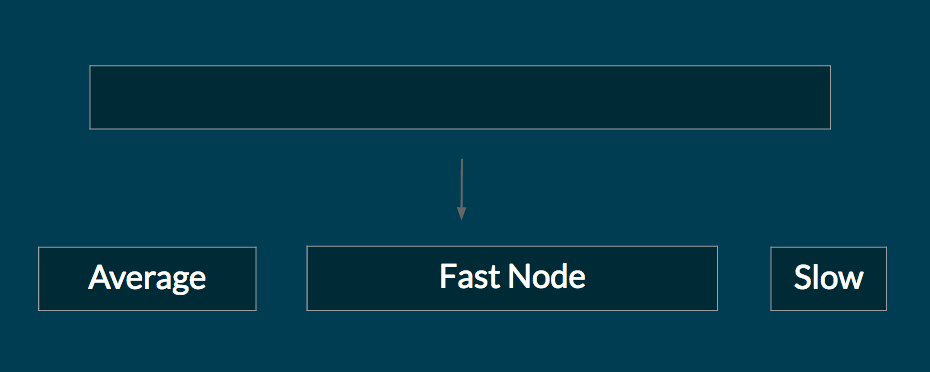

In many clusters, some nodes are faster than other nodes. This could be because the cluster is heterogeneous, and some machines are better than other machines. Or it could be because a node is facing a temporary slowdown (possibly because other users are sharing the underlying machine).

When the user initializes a Cluster, we profile each node by running loops of arithmetic operations and memory allocations. The results for each node is shared across the cluster. The sequence library then distributes data proportional to the nodes' performance. For example, suppose we have a 2 node setup, node 1 takes 0.2 seconds to run the profile code, and node 2 takes 0.6 seconds to run the profile code. If the user initializes a Sequence of size 100, 75 of the elements will go to node 1, and 25% of the elements fo to node 2. The figure below illustrates this.

This feature is currently experimental. We have not yet tested the sequence on a cluster with different machines. However, theoretically this is a very powerful technique to balance load in real life clusters.

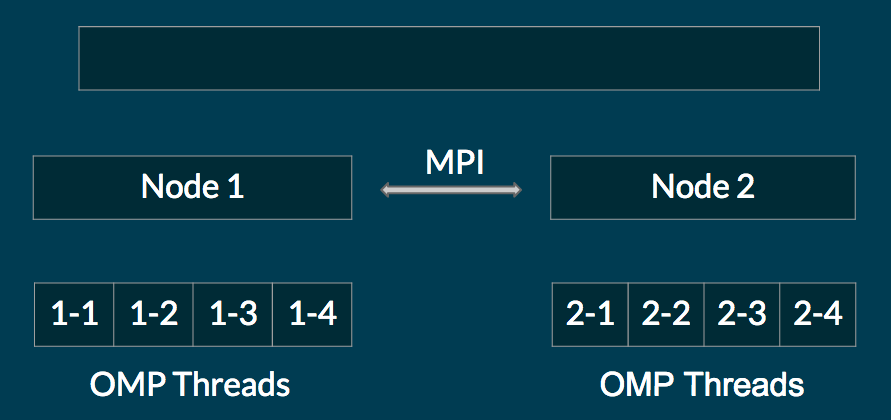

MPI - OpenMP Hybrid Architecture

We use MPI to communicate between nodes, but within a node we spawn openMP threads to perform computations. The number of openMP threads we spawn is typically 2 times the number of cores, so that each thread maps to a unique hyperthreaded context. This is a common paradigm (for example, see http://openmp.org/sc13/HybridPP_Slides.pdf). The architecture is illustrated in the diagram below.

Why MPI? First, many large clusters don’t have shared memory. So using OpenMP would not be feasible (or could be very slow). Even on clusters that support shared memory, MPI allows for a more fine grained control of communication between nodes, and of where memory is allocated. This allows us to minimize communication between nodes.

Why OpenMP? A single node usually has a fast shared memory architecture, which OpenMP is suited to. Using MPI would typically lead to a larger communication overhead, especially in broadcast functions like AllToAll, because we have more virtual nodes. We observed this in our tests: a pure MPI architecture was not able to scale well beyond 8 6-core CPUs, while the hybrid implementation scaled well on up to 16 6-core CPUs (the maximum number tested).

External Devices

In our main website, and in an email to Kayvon, we mentioned that we will try our best to integrate the Xeon Phi into our library (although we mentioned that we will not guarantee this). We spent many hours trying to integrate the Xeon Phi, but we were unsuccessful. The main issues were running a job that uses MPI and the Phi simultaneously, and offloading lambda functions to the Phi. Integrating the Phi would be very exciting, so we leave this for future work.

Map/Tabulate/Transform Implementation

After the Sequence has been setup and allocated correctly, tabulate is a pretty easy function to implement. Each nodes examines each chunk it is responsible for, and assigns the values specified by the tabulate function to each element in the chunk.

Implementations of Map and Transform are conceptually similar (though map requires copying a lot of data because we are producing a new sequence).

Reduce/Scan Implementation

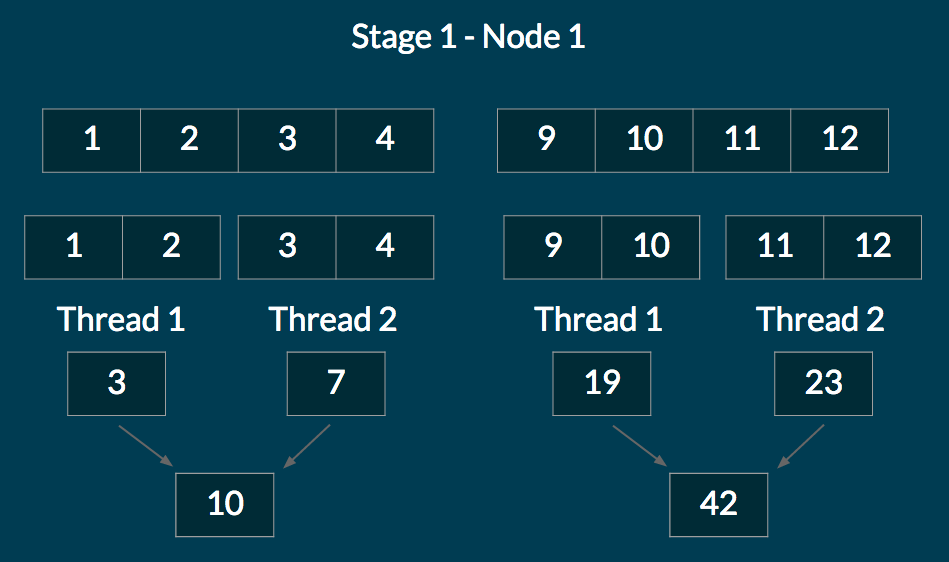

We explain how reduce works using an example. Suppose we have a cluster of 2 nodes. We allocate a sequence of size 16: (1, 2, 3, …, 16). We chunk the sequence into 4 parts and distribute so that node 1 gets (1, 2, 3, 4) and (9, 10, 11, 12), and node 2 gets (5, 6, 7, 8) and (13, 14, 15, 16).

In the first stage of the reduce, each node performs a reduce on its own chunks. Multiple threads work together to reduce each chunk. At the end of this stage, each node has reduced values for each chunk it is responsible for. The diagram below illustrates this stage for Node 1.

The nodes then collectively communicate the partial reduces for the chunks they were responsible for. So each node has access to the reduced values for every chunk in the sequence. The chunk values are sorted in linear time (possible because the number of nodes fits in an array). Each node reduces over the chunks to get a final reduced value. The diagram below illustrates this stage for Node 1.

The first half of Scan and reduce are roughly the same. However, after receiving partial reduces from the other nodes, Scan has to do some work applying the partial reduces to the chunks that the node is reponsible for. Doing this efficiently is tricky, please see our code for more details. Of particular note is that our code runs though elements in the sequence twice, and so would do about 2 times greater work than an optimal serial implementation of scan that runs on a single core. This is an improvement over the Scan code in homework 3, which runs through the array 4 times (admittedly for the sake for computing efficiently on the GPU).

Results

We have two categories of results to outline. The first of these deals with the performance of our parallel code with respect to serial code. These results mostly serve to highlight the effectiveness of our approach (i.e., work balancing, etc.). The second category compares our parallel implementation to other parallel implementations, in particular Thrust for GPU-level parallelism using a similar, functional programming style.

Effectiveness of Approach

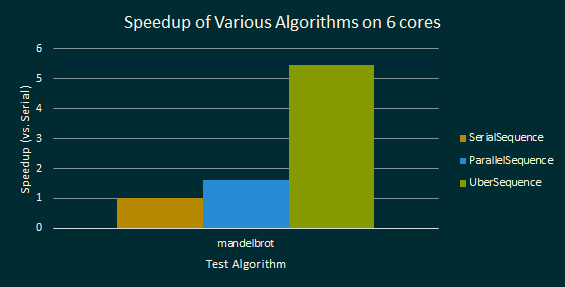

First, some definitions: SerialSequence is a completely serial implementation of the sequence abstraction (that does not have any MPI, openMP calls). ParallelSequence is our initial parallel implementation. UberSequence is our parallel implementation of the abstraction with the optimizations explained above.

Results for Mandelbrot benchmarks for difference Sequence algorithms are shown below. The benchmark generates the Mandelbrot set in a 5,000 by 2,000 sized grid, going up to 256 iterations per grid cell.

In the first test, performance was measured on a 6-core GHC machine. The parallel implementations used up to 12 hyperthreaded execution contexts. Results are shown below: Notice, in particular, that UberSequence obtains pretty good speedup.

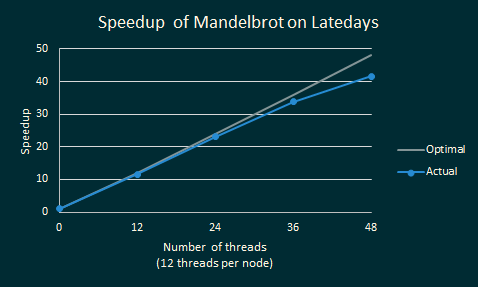

The graph below shows how the speedup for UberSequence on Mandelbrot varies with the number of LateDays nodes. Each node has 2 CPUs * 6 cores * 2 hyperthreaded contexts. A value of 1 on the y-axis means that the sequence ran at the same speed as SerialSequence. As we increase the number of execution contexts, we still manage to get near-optimal speedups!

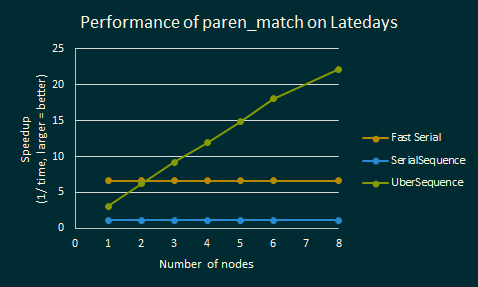

Below is the same analysis for paren_match, an algorithm that computes whether

a sequence of parentheses is well-matched. We ran paren_match on a balanced

sequence of parantheses with 200 million elements. Note that Fast Serial is an

optimized (non-parallel) sequential code that does not use the sequence

abstraction. Fast Serial does not do the same computations, and avoids the

overhead of the sequence library. As such, it performs better than any of the

sequence libraries on a single node.

Paren match is a much more difficult problem to have good speedups for, because it uses functions such as scan and reduce which are much more difficult to parallelize, and because the optimal solution is very different from the solution using the Sequence abstraction.

UberSequence starts off slow, but it scales pretty well across nodes. The speedup is almost linear up to 8 LateDays nodes.

We ran paren match on different instance sizes, and the results were roughly similar.

Comparison to Thrust

After determining that our approach was effective at load balancing the work to achieve the optimal speedups on a cluster, we turned our attention to seeing how well it compared to alternative parallel frameworks, in particular CUDA Thrust.

For all of our comparisons, we used 4 nodes on Latedays with the UberSequence

implementation, and the NVIDIA GTX 780 on ghc41.

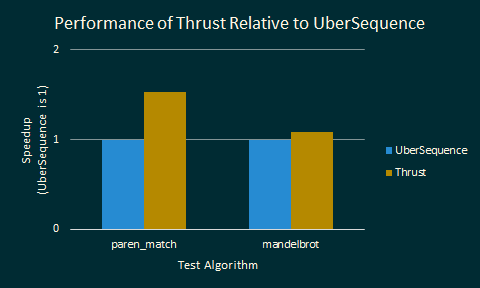

We were dismayed to find out that Thrust on a single GPU performed better than Lambda++ on an entire cluster of computers. Here are the actual speedups:

These tests are comparing the performance of both mandelbrot and paren_match

for Thrust relative to the baseline performance of Lambda++. Higher bars

indicate larger speedups. A couple of notes are relevant here.

A single NVIDIA GTX 780 is much cheaper and much more energy efficient than 8 Latedays nodes. It seems like the GPU is a much better choice than a cluster for a sequence library.

We did not vectorize (use SIMD) our code for Lambda++, which would probably make Lambda++ significantly faster.

Thrust has been tuned by experts for optimal performance on GPUs. Our code for reduce and scan could very likely be optimized, considering that UberSequence does only about 2 times better than SerialSequence on

paren_match.

Additionally, GPUs cannot handle large data sets without expensive transfers of data back and forth from main memory. Lambda++ effectively gives you access to a very large memory buffer (combined from nodes across the cluster) to solve much bigger problem sizes in-memory.

Lastly, Mandelbrot and paren_match are pretty amenable to GPU parallelism. The

compute tasks are symmetric, which means that a GPU would achieve high

vector lane utilization. For more complex tasks, the GPU could easily be

up to 30 times slower, but we don’t expect to see similar slowdowns in

Lambda++.

In the future, we would want to compare Lambda++ with other cluster level parallelization frameworks like Apache Spark.

References

We referenced a number of resources while writing Lambda++, including

- 15-210’s

SEQUENCEdocs, which describe the semantics of the various higher order functions likemap,reduce,scan, etc. - The Thrust documentation, available at

- Information about the knapsack problem

- Specs for NVIDIA GTX 780

Effort Distribution

We feel that equal effort was demonstrated by project members throughout. We both had a great time working on Lambda++ and are proud of how it turned out!

Lambda++: Functional Sequence Library for C++

Lambda++: Functional Sequence Library for C++